- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: From thin air

- Article Subtitle: Biography without context

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Was Katharine Susannah Prichard one of those present at the first meetings of the Communist Party of Australia (CPA), or not? Did she or didn’t she later pass intelligence to the Soviets, as charged by historians of ASIO Desmond Ball and David Horner? What difference would it have made to have had Lesbia Harford’s full queer oeuvre before the Australian public when it was written? Why didn’t Dymphna Cusack join the CPA if, as this book asserts, her politics were just as far left as Frank Hardy’s? How aware was Eleanor Dark of First Nations activism when writing The Timeless Land (1941)? Politics sit at the heart of Australian literary history, but a raft of questions remain for contemporary readers.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Nicole Moore reviews ‘Inconvenient Women: Australian radical writers 1900-1970’ by Jacqueline Kent

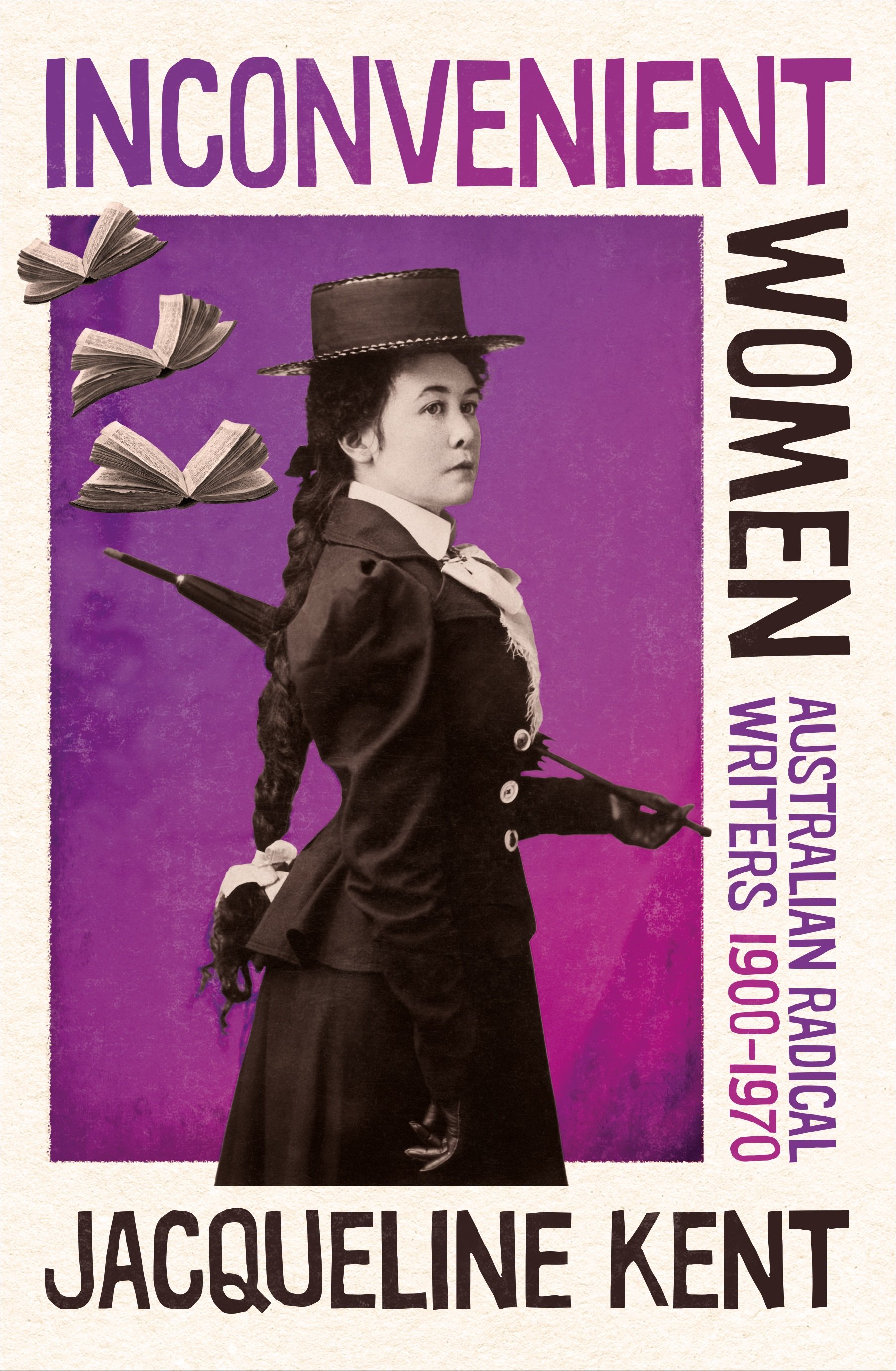

- Book 1 Title: Inconvenient Women

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australian radical writers 1900-1970

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $34.99 pb, 311 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781742237503/inconvenient-women--jacqueline-kent--2025--9781742237503#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Few current writers position themselves as heirs to an Australian tradition. More common are iconoclasts and dissenters, especially First Nations writers and those from communities that have sharp questions for a white, heterosexual national past. More common still are writers who inhabit a present without an Australian literary past; whose horizons are American, British, or wider. Literary memory was more valuable, perhaps, when a writerly education propelled cultures dependent on print for continuity. With the humanities savaged by university management, ignored by industry and abandoned by government, literary studies is now a battered punching bag for critics of what Stanley Fish long ago characterised (and praised) as properly ‘useless knowledge’.

Books like this one, then, are charged with bridging this gap. Jacqueline Kent’s collective biography of twentieth-century radical writers joins a long line of Australian prosopography that looks to these authors for inspiration, especially as feminists. Even the subjects of this book themselves contributed. For the sesquicentenary in 1938, Flora Eldershaw edited The Peaceful Army, subtitled ‘A memorial to the women pioneers of Australia’, its featured white writers including young, prize-winning novelist Winifred Birkett surveying older women’s work. Miles Franklin and Dymphna Cusack’s satirical play Call Up Your Ghosts (1945) conjured phantom Australian writers to target the country’s literary amnesia.

Kent’s book prompts us to consider whether the legacy of such feminist endeavour remains alive, and the ongoing success of second-wave efforts to reintroduce Australian women writers to readers. Drusilla Modjeska’s Exiles at Home (1981), Carole Ferrier’s As Good as a Yarn with You (1992), and Susan Sheridan’s Nine Lives (2011) are just some of the breakthrough group biographies and collections that did so. Two generations since have taken up their work, leading to the enormous labour behind many individual biographies, a body of literature to which Kent added her prize-winning profile of influential editor Beatrice Davis in 2001.

In her Acknowledgements, Kent begins by thanking this group of scholars, while singling out only Stuart Macintyre’s two-volume history of the CPA (1998, 2022) for mention. Inconvenient Women is a slim synthesis of their work; it is clear, uncontentious, wide-ranging. Since we are not introduced to the insights of younger scholars, and Kent references little current scholarship and very little archival material, it is hard to identify Kent’s own contribution, with a citational apparatus too frail to illuminate her research.

Letters between writers appear without mention of their repositories and the Select Bibliography is idiosyncratic rather than representative. Discussion of writers’ ASIO files cites only the National Archives of Australia’s fact sheet – a guide on how to access them – rather than the files themselves, or even Fiona Capp’s lively exegesis in Writers Defiled (1993). Some of the description, moreover, is material imported from other histories – sometimes pages at a time. Indeed, whole chapters are based on perhaps two or three sources only, unmediated by Kent’s contributions or analysis.

Eleanor Dark, 1945 (photograph by Max Dupain via Wikimedia Commons)

Eleanor Dark, 1945 (photograph by Max Dupain via Wikimedia Commons)

Synoptic accounts can be tremendously useful if they fuse the long view with the acute. Unsure of its moment, Inconvenient Women is apologetic about some writers, dismissive of others, and wrong about quite a few. The imperative of national cultural and social progress – so central to the thinking, writing, and work of Franklin, Dark, Nettie and Vance Palmer, Marjorie Barnard, Kylie Tennant, and even communists such as Dorothy Hewett and Jean Devanny, as well as Oodgeroo and Faith Bandler in different ways – has long faded for readers; Australia is no longer a determining frame. Kent focuses on these writers’ political beliefs and lives, and occasionally on the life of their writing in the world. But there is no address to the present, no commentary on why we need these stories now – apart from asides about the anodyne Facebook boosterism of women writers today. Were these writers truly radical? What difference did they make? Or were they just ‘inconvenient’ – minor obstacles for a society that has developed despite rather than because of their lives and work?

The final chapter attends to First Nations women’s writing and broader Indigenous activism from the late 1950s through to the 1967 referendum and is focused on Oodgeroo, Margaret Tucker and Bandler, though there is no mention of Bandler’s own writing or Oodgeroo’s connection to the Brisbane Realist Writers Group, a grassroots Cold War endeavour. Similarly, this chapter sits on its own, without a final note or epilogue to connect the activism and literary achievements of these writers to the previous chapters’ histories of struggle. Apart from some reference to Oodgeroo’s famous first poetry collection, We Are Going (1964), and Tucker’s autobiography, If Everyone Cared (1977), this chapter appears to rest on Googleable public histories. The transformative analysis of current First Nations critics, reading the work of all these writers, would have shifted the view markedly. I find myself wondering whether Kent’s version of this history, while seeking to return these writers to prominence, serves also to obscure the labour and identities of the beleaguered researchers who continue to champion them.

Biography that speaks to broad audiences can make complex history deeply human, felt, and realisable in ways that bring the past close: that is why it sells. But are readers now so averse to witnessing the labour of research that books must treat the past as just a story to be told, conjured seemingly from thin air?

Chris Wallace’s critique of Kent’s The Making of Julia Gillard (2010) was that it stayed on the surface, offering only ‘description without analysis’. For a prime minister, this was arguably politic and a reflection of Gillard’s own understandably guarded persona. But for these treasured, much discussed, rousing literary lives, the triumphs and failures at stake deserve to be weighed properly; to be encountered anew in fresh contexts.

Comments powered by CComment