- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Shaming hyenas

- Article Subtitle: When poetry resounded

- Online Only: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

In his 1928 collection of poems, Odd Jobs, Ernest ‘Kodak’ O’Ferrall caricatures recitation as an onerous entertainment that has passed its use by date:

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Chris Lee reviews ‘The Wild Reciter: Poetry and popular culture in Australia 1890 to the present’ by Peter Kirkpatrick

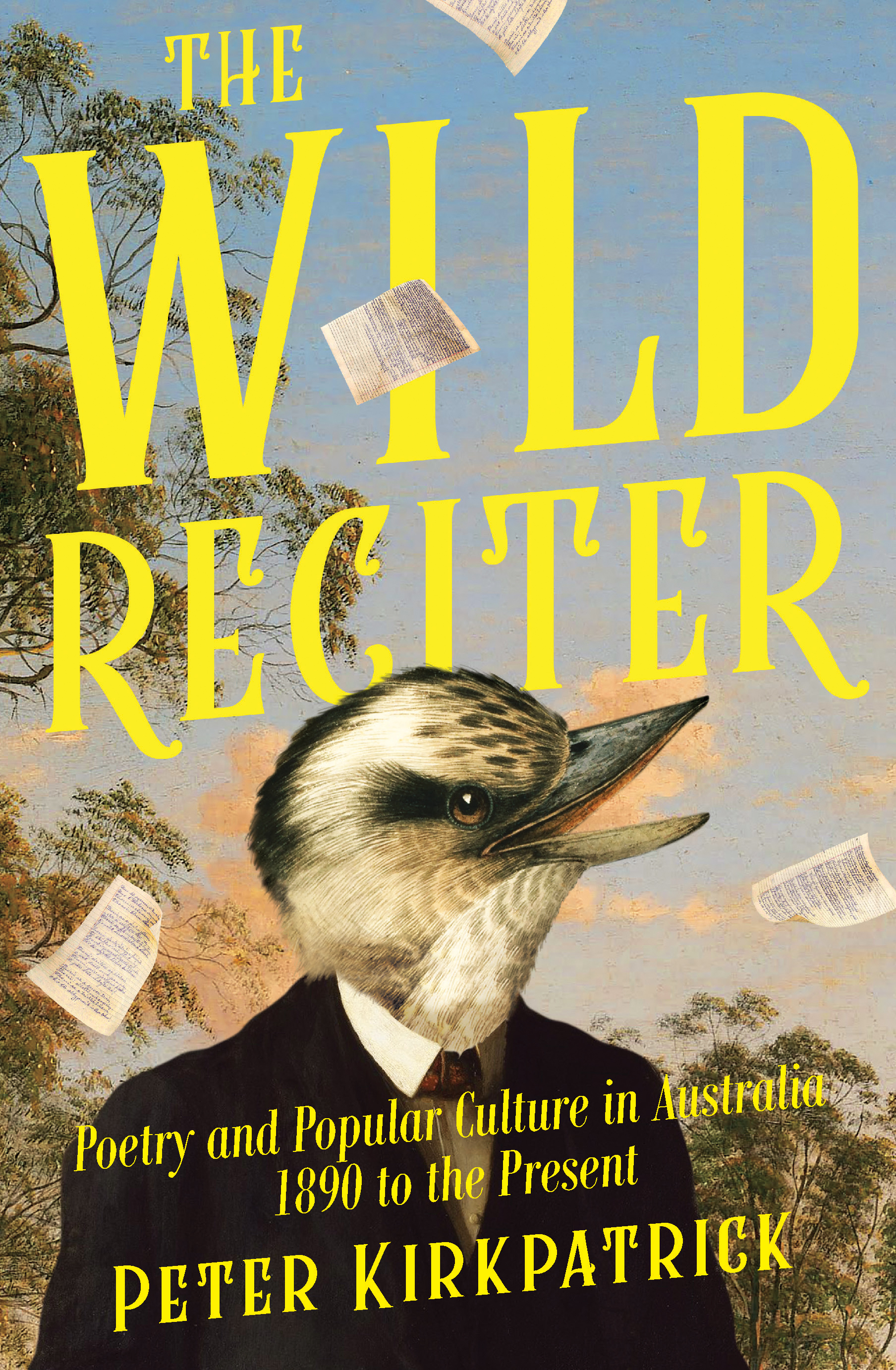

- Book 1 Title: The Wild Reciter

- Book 1 Subtitle: Poetry and popular culture in Australia 1890 to the present

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $34.99 pb, 344 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780522880298/the-wild-reciter--peter-kirkpatrick--2024--9780522880298#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

‘Kodak’ acknowledges the enthusiasm of those who plied the trade and presumes upon the tired familiarity of his readers with their histrionic modes of address.

Peter Kirkpatrick’s stimulating account of the uses of poetry in Australia from 1890 to the present begins by tracing the nineteenth-century penchant for recitation back to the previous century’s practice of elocution or voice training. The skillset sought a desirable accent, which in the manner of Eliza Doolittle might conceal the speaker’s lamentable origins. Elocution helped popularise the recitation of poetry in homes and schools and it provided access to respectable modes of public presentation and performance for middle-class women. Recitation promoted particular ways of performing poetry just as it favoured particular forms of poetry in the process of disseminating middle-class values and moulding imperial British citizens. It provided a rhetorical training which was itself part of a larger project of self-presentation inspired by what Henry Lawson would call the ‘desire to rise’ in the estimation of society and to prosper in a new world of opportunity.

O’Ferrall’s comic reservations suggest that by the 1920s the wild reciter’s appeal had run its course. But in its day the already familiar written word spoken aloud with appropriate gesture by a skilled performer could be inspiring, moving, and entertaining. A wide variety of audiences, some literate, some not, could assemble in public parks, local halls, athenaeums, schools of arts, mechanics institutes, music halls, clubs, and theatres. An appreciation of recitation, along with an understanding of a number of other popular uses of poetry through time, changes the ways we might think about the role that poetry has played in Australian society. How has poetry been produced, read, practised, performed, and distributed? By what kind of people and through what sort of institutions? How has this rich and complex history transformed poetry and those who read and recite it? The Wild Reciter investigates these questions in an attempt ‘to understand the interrelationship that necessarily exists between “poetry” as a specialised genre of interest to a few, and poetry as a familiar art form accessible to everybody, as close as graffiti or the lyrics of a Taylor Swift song’.

Kirkpatrick’s ambition is a wider history but his enquiry takes the form of a dozen case studies from the 1890s to the present moment. The initial chapter on recitation is followed by an enquiry into the influence of touring American Wild West shows and displays of rough riding on the composition, reception, and reinvention in more recent times of Banjo Paterson’s most famous poem, ‘The Man from Snowy River’. This chapter begins with a brief but useful history of horse shit, of which Marvellous Melbourne produced 80,000 tons each year. From there it moves onto Banjo’s beloved quadrupeds through page and stage, concluding with the spectacle of the opening ceremony of the 2000 Sydney Olympics.

Subsequent chapters look at the influence of stage, screen, popular music, radio, and the press on the relationship between ‘light’ or popular verse and ‘serious poetry’. Case studies feature silent film, jazz, Smith’s Weekley (1919-50), Railroad (1924-35), ABC radio’s poetry program Quality Street (1946-73), crime fiction, the literary festival, media celebrity, and the bestseller. In the process, the book offers insightful discussions of the work of Paterson, C.J. Dennis, Raymond Longford and Lottie Lyell, Lesbia Harford, Kenneth Slessor, Ernest Arthur Chapman, John Thompson, Ronald McCuaig, Yevgeny Yevtushenko, Bob Dylan, John Laws, Rod McKuen, Clive James, Dorothy Porter, and Evelyn Araluen. A diverse cast of supporting actors supplements the list.

Kirkpatrick’s prose is peppered with inventive metaphor, wit, and ductile diction. Style and method mimic the subject matter, drawing tropes, allusions, and phraseology from an eclectic mix of high and popular culture. Insightful textual analysis of the kind now rarely taught is blended with well-chosen historical scholarship, spiced with primary sources of social and cultural interest. The formal analysis and historical narrative are complemented by a continuing parade of fascinating, often genuinely humorous anecdotes and examples. This is an informative and entertaining book which uses its richly imagined case studies to pose provocative alternatives to well-worn versions of Australian cultural history.

The Wild Reciter concludes with a clear distinction between formal invention, linguistic innovation, and originality – a form of high or ‘serious’ poetry, and the embodied oral performance of verse which is more a function of the relationship between the reciter and the audience. That relationship ensures that ‘to make your name you need to speak up, aloud and proud, and be heard by others in your community. Success is based on your audience’s assumptions about what constitutes a suitable eloquence … Complete originality, if such a thing exists, is less important than the reanimation of special ways of speaking – communal forms of rhetoric – that are acknowledged and affirmed by the audience’. Alas, it is an insight that the current US president understands more effectively than his opponents: feeling trumps reason; mythology eclipses history. That perhaps is reason enough to side with the author when he laments the end result of such a circus: the consignment of serious poetry to the margins.

Comments powered by CComment