- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Gascoigne Puzzle

- Article Subtitle: Writing around a life's core

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Rosalie Gascoigne seems exemplary of the popular fable of the late-blooming woman artist. Famously, her first exhibition was in 1974, when she was fifty-seven. This swiftly led to national recognition, then international exposure at the 1982 Venice Biennale. So this is a story for the times. But the achievement of Nicola Francis, the artist’s biographer, is to unpack how, in Gascoigne’s case, artistic success in later life was the result of long, careful training in two other creative pursuits: flower arranging, as taught by the English authority Constance Spry; then, crucially, training and a thriving career in the most radical form of ikebana, the Japanese art of flower arrangement, through the Sogetsu School popularised in Australia by Norman Sparnon.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Julie Ewington reviews ‘My Own Sort of Heaven: A life of Rosalie Gascoigne’ by Nicola Francis

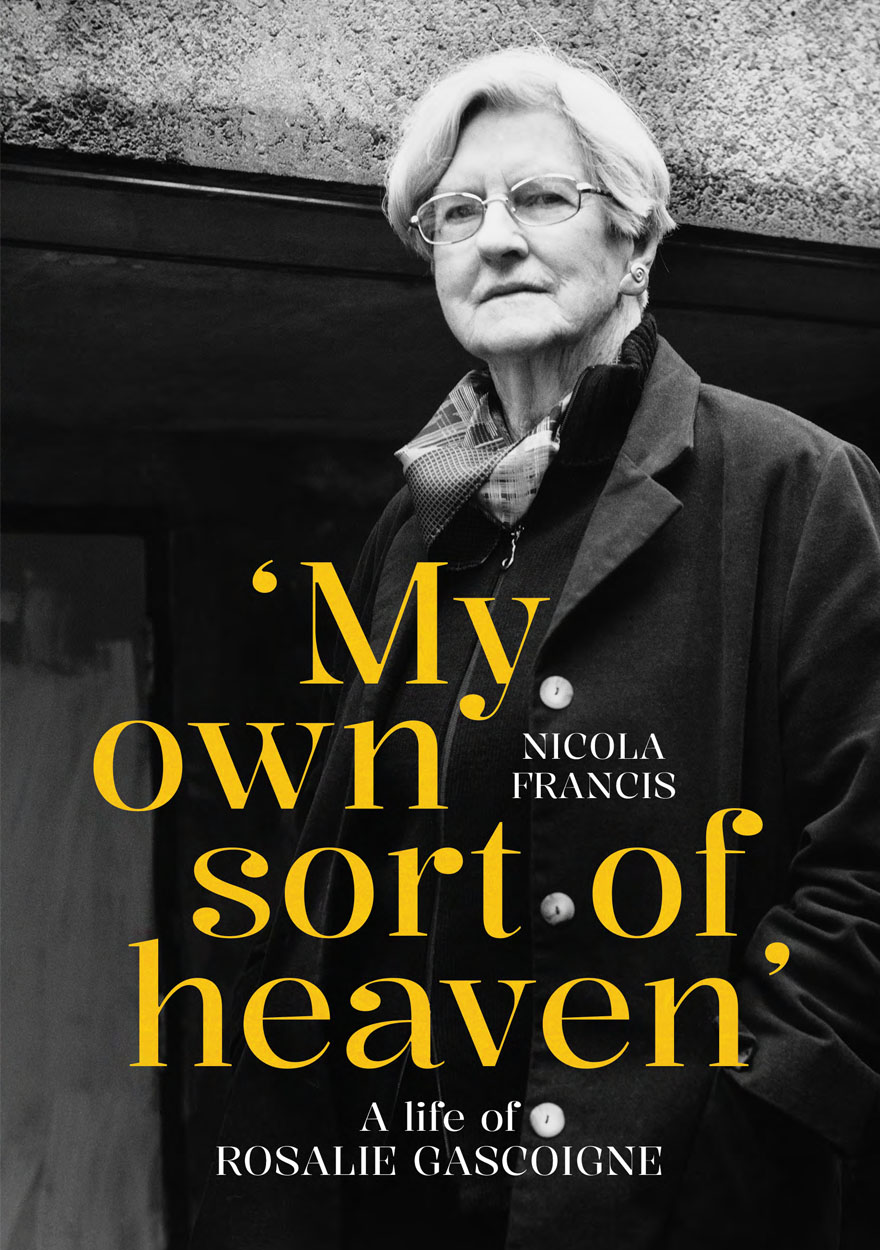

- Book 1 Title: My Own Sort of Heaven

- Book 1 Subtitle: A life of Rosalie Gascoigne

- Book 1 Biblio: ANU Press, $85 pb, 410 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781760466558/my-own-sort-of-heaven--nicola-francis--2024--9781760466558#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Francis draws her picture of the artist through two main lines. First, she is attentive to Gascoigne’s social contexts. Starting in Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand, from her birth in 1917, Francis describes how family traumas, and persistent anxiety in the family about their sliding social status, dogged the Walker family. After she moved to Australia in 1943 to marry S.C. Gascoigne, the eminent astronomer usually known as Ben, Gascoigne navigated of the fast-developing cultural and social milieu of postwar Canberra, where she lived for the remainder of her life (she died in 1999). Her picture of the nascent cultural scene in Canberra is fascinating: Gascoigne’s commissions to make regular flower arrangements for the Academy of Sciences and the Australian National University, among other important institutions; her friendships with local artists, crucially painter Michael Taylor; and her enduring connection with James Mollison, then developing the Australian National Gallery in the lead-up to its opening in 1982. All in all, Gascoigne gradually became a true Canberra insider, enjoying the opportunities the growing national capital offered.

The second line through this biography is Francis’s relentless, even unsparing, examination of Rosalie’s repeated claims to be an outsider, someone who felt apart, even when she led a conventional life, even when she had a loving family and, later, great success in her chosen fields. Francis’s sceptical take on the artist’s well-honed mythology of her own creation is refreshing, especially when set against her scrupulous delineation of Gascoigne’s formative social contexts. I am not sure that she solves this conundrum, but she shows how Gascoigne’s borrowing of Picasso’s idea of ‘the born artist’ enabled her to explain her drive to make, her way of exploring sense of the world.

A wealth of material is now available on this major artist, most importantly the marvellous catalogue raisonné by her son Martin Gascoigne, published by ANU Press in 2019, freely available to download (like this book). Martin continued the work of cataloguing Gascoigne’s work started by her husband, a methodical scientist, around 1980, and his book includes a perceptive essay about his mother’s work. Martin’s interest in contemporary art as a young man helped steer Rosalie’s growing understanding through the 1960s. (Rosalie’s career was well supported by her family.)

Francis’s biography is, however, almost silent on one crucial question about Rosalie Gascoigne. What did she read? Biographies, it seems; she was interested in people’s stories. But Francis doesn’t say which people. Even more puzzling, the word ‘poetic’ is often invoked about Gascoigne’s work – but which poets mattered to her? Martin is more useful, noting that Rosalie could quote from English Romantic poets, which in turn suggests that she was influenced by William Wordsworth’s observation that poetry captured ‘emotion recollected in tranquillity’. This seems apt: ‘emotion recollected in tranquillity’ or, more accurately, emotion structured by the refined appreciation of the natural world embodied in ikebana. ‘I am not making pictures,’ Rosalie wrote in 1997, ‘I make feelings.’ Rosalie’s long friendship with eminent Canberra poet Rosemary Dobson, an occasional companion on collecting trips around the Monaro, also suggests familiarity with the poets’ world. I would have liked to know more about how this openness to poetry affected the work: its allusiveness, its rhythms, its purposeful reiterations, the ventures into what looks like concrete poetry.

That brings me to a more troubling absence: there are no images of Gascoigne’s art, which, after all, were what made her celebrated. Francis notes images were not available because of ‘copyright complexities’, pointing readers to Martin’s catalogue raisonné. Perhaps that is why there are no substantial discussions of Gascoigne’s oeuvre, which was the crowning achievement of her life; no real sense of how Gascoigne’s lyrical, idiosyncratic way of putting found materials into refined compositions was completely original. It seems Francis is writing around the core of the life, rather than through it. One telling detail: the great majority of the book, until page 258, takes Gascoigne from birth (and before, with her family’s history) to that first exhibition in 1974 in Sydney; the great triumphs of her artistic career, and those last twenty-five years, are covered in a scant sixty-five pages.

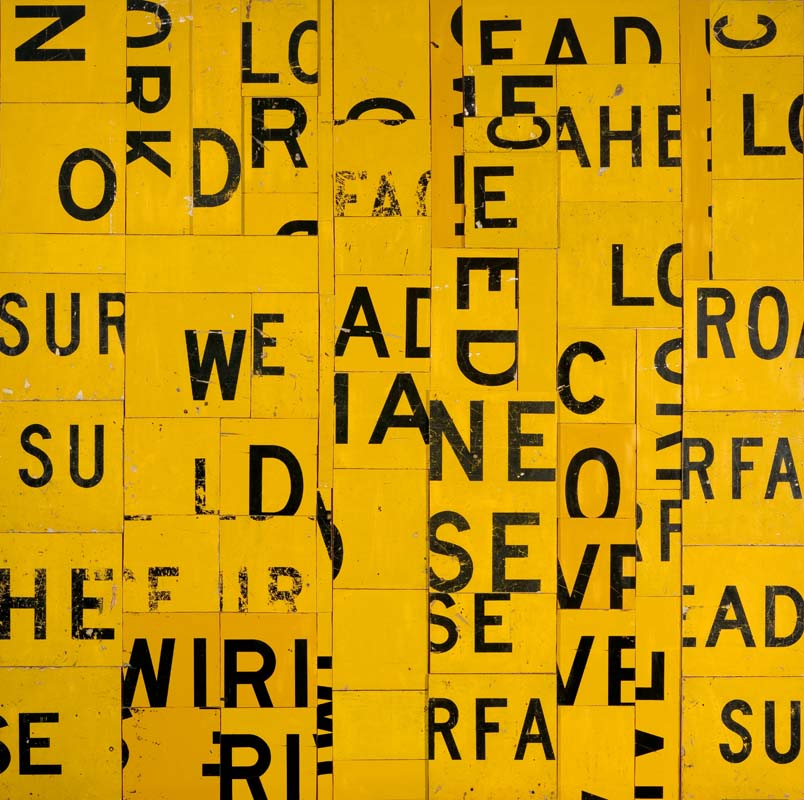

The awkward addition to the original PhD thesis of an Epilogue about ‘issues that affected her [Gascoigne] in the context of other works by women artists’ underlines Francis’s unwillingness to engage with Gascoigne’s work. Even a few examples would have illuminated the copious material she has painstakingly amassed: Enamel ware (1976, Art Gallery of New South Wales), acquired for the Gallery by Daniel Thomas from the first Sydney exhibition, with its summary of the Monaro scavenging; the breathtaking Piece to walk around (1981, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney), exemplifying how Gascoigne brought the rigorous sensibility of ikebana into conversation with contemporary seriality, and, I would argue, manifested the stoicism of Gascoigne’s generation to which Francis refers throughout the text; and consideration of a retro-reflective piece, such as Lamp lit (1989, QAGOMA), would have shown how the colour yellow followed Gascoigne throughout her life, and how she sought it out. These were threads that tied the life together.

Rosalie Gascoigne / Australia 1917-99 / Lamp lit, 1989 / Retro-reflective road signs on hardwood / 183 x 183cm / Purchased 1990. Mrs J.R. Lucas Estate in memory of her father John Robertson Blane / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Rosalie Gascoigne / Photograph: QAGOMA

Rosalie Gascoigne / Australia 1917-99 / Lamp lit, 1989 / Retro-reflective road signs on hardwood / 183 x 183cm / Purchased 1990. Mrs J.R. Lucas Estate in memory of her father John Robertson Blane / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Rosalie Gascoigne / Photograph: QAGOMA

That said, My Own Sort of heaven is copiously illustrated with Gascoigne family photographs, and a wealth of fascinating images showing the New Zealand and Australian contexts of Gascoigne’s life, the result of formidable research. I do have several notes on the not entirely satisfactory transition from thesis to book: ANU Press’s usual high standards have let the author down with some lamentable lapses in proofing, including several substantial errors: MOMA and the Metropolitan Museum of Art are confused, and the incorrect claim in the Epilogue that Margaret Preston was among a cohort of Australian artists with family wealth, which was not the case in her early years, when Preston’s friend Gladys Reynell paid for her overseas travel.

Australian visual artists have been well served by their biographers – Brenda Niall and Helen Ennis come to mind. Nicola Francis brings a special perspective to this biography, drawing on her own family history in Aotearoa New Zealand and on comparable experiences of migration across the Tasman. As a long-time resident of this country who is also a New Zealander, she has a special scepticism about migration narratives. She argues persuasively that Rosalie Gascoigne’s well-rehearsed personal narrative was mostly received uncritically, which I believe is correct. She would be interested to know that I did see Canberra art school students in the 1990s being equally suspicious of Gascoigne’s blithe account of her creative processes.

The work of biography is to create new narratives about lives: in this case, who Rosalie Gascoigne was, and what she did. My Own Sort of Heaven goes a long way to filling in the Gascoigne puzzle. Hester Gascoigne, the artist’s daughter, concludes her introductory note to this biography by remarking ‘May there be many more!’ I can only concur.

Comments powered by CComment