- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letters

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A sense of not belonging

- Article Subtitle: More letters from Shirley Hazzard

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Biographers nearly always rejoice to find a bundle of letters. If both sides of a correspondence have survived, it doubles the pleasure. At its best, an exchange that was maintained over a long period will illuminate personality, time, and place. Love letters are probably the most highly prized. Whether or not the lovers have the gift of words, their closeness in a relationship brings a sense of reality. Readers of some self-revealing intimate letters may feel like intruders, uninvited watchers at a private theatre for which they didn’t buy a ticket.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Brenda Niall reviews ‘Expatriates of No Country: The letters of Shirley Hazzard and Donald Keene’ edited by Brigitta Olubas

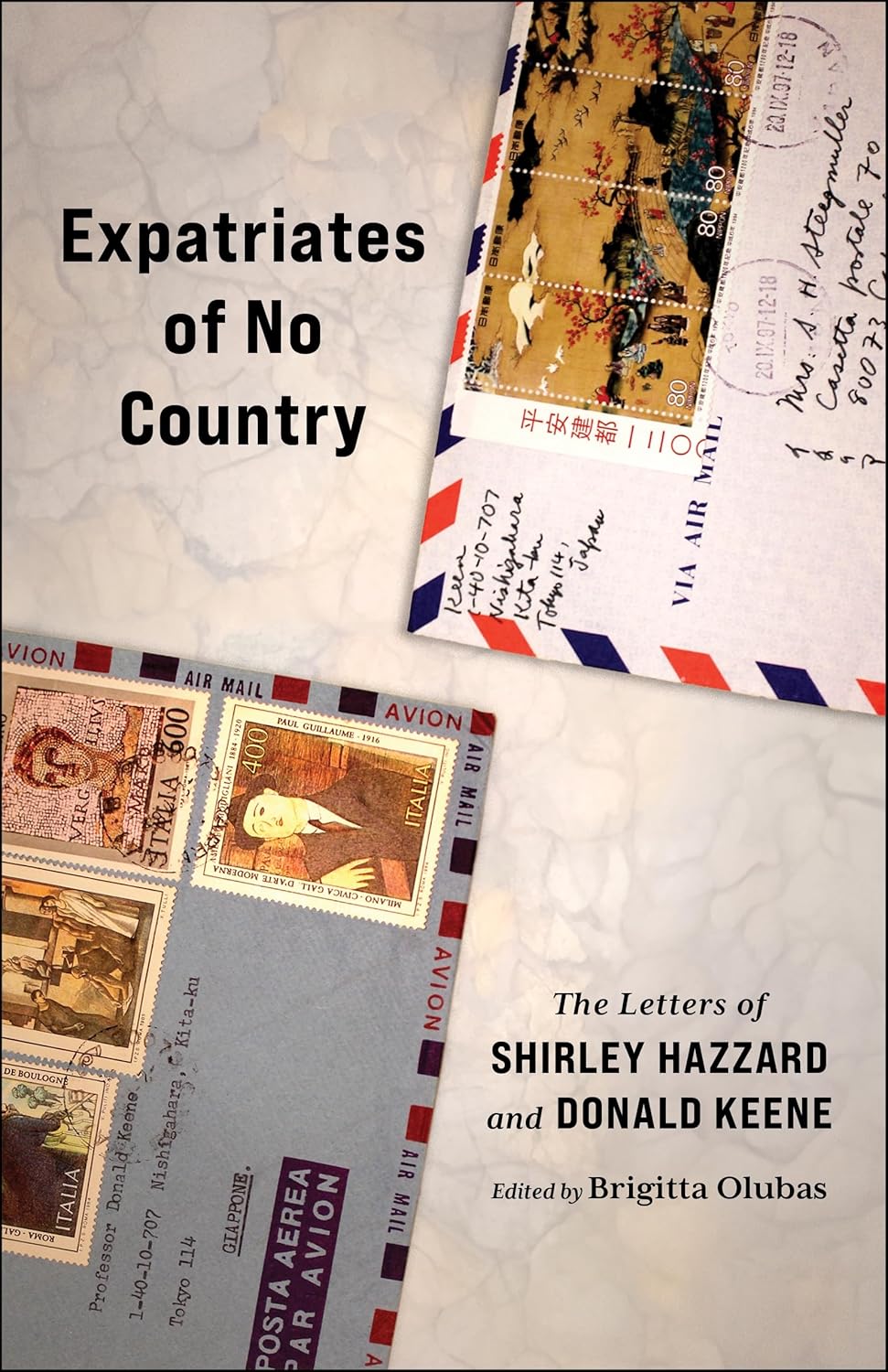

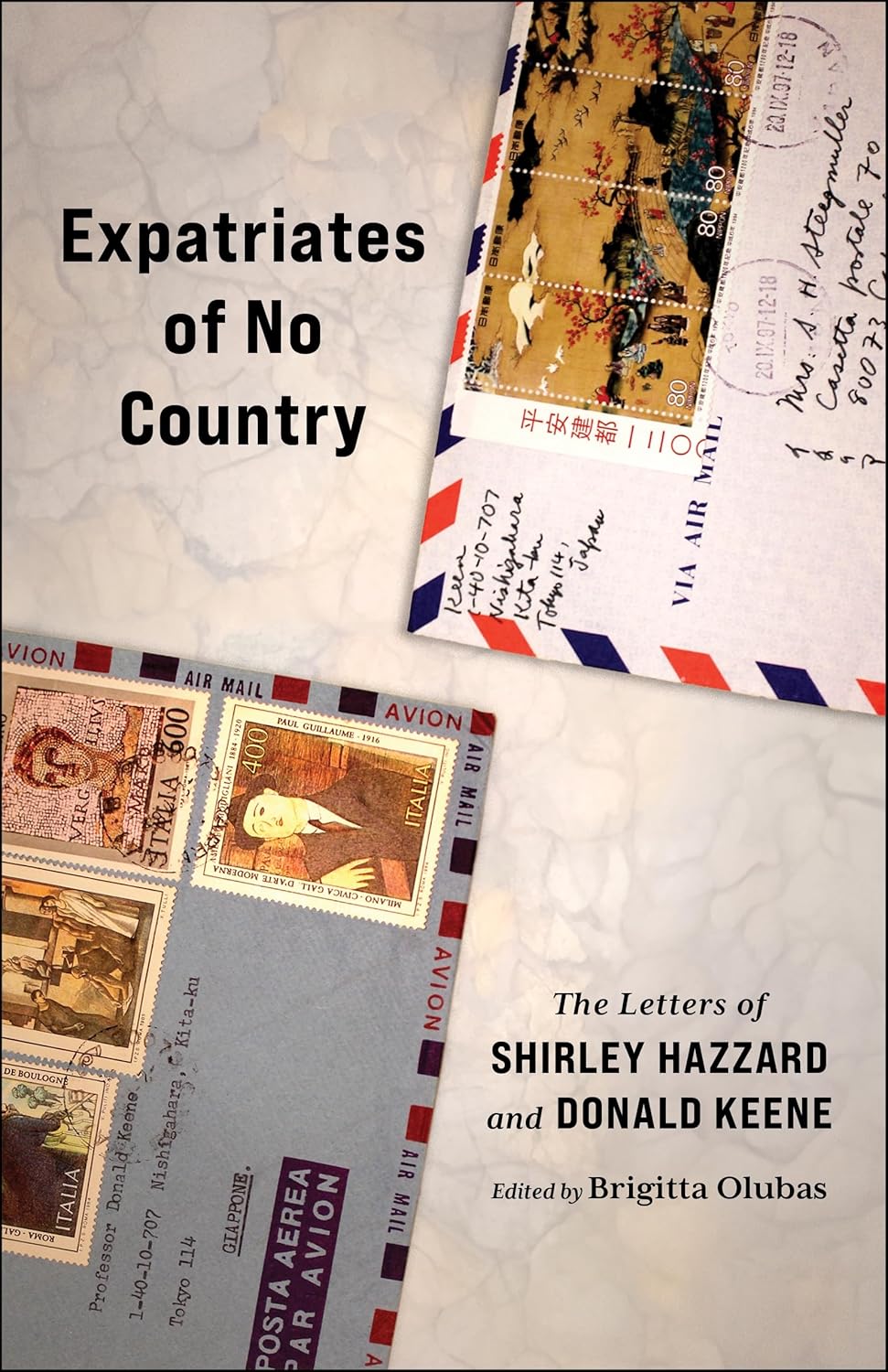

- Book 1 Title: Expatriates of No Country

- Book 1 Subtitle: The letters of Shirley Hazzard and Donald Keene

- Book 1 Biblio: Columbia University Press, US$22 pb, 216 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780231214452/expatriates-of-no-country--shirley-hazzard-donald-keene--2024--9780231214452#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Some letters, however, invite an audience. Whether the link between the correspondents may be strong or slight, many letters show that the writers enjoy the game of words for its own sake. The bravura comic performances of Gwen Harwood, one of Australia’s most brilliant letter writers, are mostly about Gwen. Readers of Harwood’s correspondence, in Gregory Kratzmann’s superbly edited collection, A Steady Storm of Correspondence (which I reviewed in the November 2001 issue of ABR), need not feel uncomfortable. Gwen wanted us to hear her voice. Was that true also of novelist Shirley Hazzard, of whose letters biographer Brigitta Olubas has published two volumes? They follow the publication of Olubas’s splendid, shrewd, and richly documented biography Shirley Hazzard: A writing life (2022).

Hazzard and Harrower, which was reviewed in these pages by Peter Rose (ABR, June 2024), is the more interesting of the two sets of letters. Both Australian-born and both novelists, Elizabeth Harrower and Shirley Hazzard were close in age, but they had very different careers. Harrower seldom left Sydney. Hazzard thought of herself as a willing exile from an Australia she scarcely knew. She had a wretched childhood in Sydney and no wish to return. The Hazzard-Harrower letters are personally revealing in ways that the writers might not have intended. Some letters show strains: Hazzard’s socially and intellectually distinguished life in Europe with her husband, a scholar of independent means, was a world away from Harrower’s humdrum suburban Sydney. Hazzard had means to write; Harrower worked in a publisher’s office. Yet Hazzard thoughtlessly delegated to Harrower many duties of caring for her mother. It looked like exploitation, and when Hazzard and her husband tried to make some recompense with the gift of a holiday in Europe, Harrower felt patronised and went home early. Nevertheless, the friendship survived. It was, as Peter Rose remarked, ‘sisterly’.

The second collection, Expatriates of No Country, is untroubled by conflict of any kind. Hazzard’s letters to and from Donald Keene, an elderly and distinguished scholar of Japanese language and literature, lasted for more than thirty years. They are more about his work than hers. He writes in a friendly style about her novels but without touching on their distinctive qualities: their narrative power, their wit, their sharp satirical edge. Hazzard’s gift for evoking place must have impressed Keene, whose accounts of his own constant travel make up a good proportion of the exchange.

Clearly, Hazzard was impressed by the intellectual weight of Keene’s writing. They met infrequently. Hazzard and her husband, Francis Steegmuller, divided their time between New York and Capri. As a young woman Hazzard had struggled. Her formal education ended in Sydney at sixteen and she later worked as a stenographer at the United Nations in New York. But these letters find her middle-aged in a degree of elegant comfort made possible by her happy marriage to a wealthy scholar.

The common thread in the Hazzard-Keene correspondence is the sense of not belonging. Hazzard returned to Australia only for short visits. Her mother, always mentally unstable, once suggested to the five-year-old Hazzard that they should both put their heads in the gas oven. Relations with her sister, Valerie, were nothing like the idealised close companionship of siblings in Hazzard’s novels. Boredom and dislike sum it up.

Although Hazzard found pleasure in the Australian landscape, it was never home to her. Italy was a delight, and she found intellectual companionship in New York. Her affinity with Keene stemmed partly from their memories of war and their appalled reaction to the atomic bomb. Late in life, Keene took out Japanese citizenship as a form of solidarity. Hazzard, who had left Australia as a schoolgirl, had a strong sense of the suffering of Hiroshima and only minimal identification with her birthplace.

Hazzard’s glacial relationship with Patrick White was probably only of minor interest to Keene, who was more at home in ninth-century Japan than in fractious Sydney. Nevertheless, Hazzard treats him to a long diatribe about White. His autobiography, Flaws in the Glass (1981), had ‘so much vindictiveness, such transmuted egotism and revenge’; his attack on Sidney Nolan was ‘unhinged’. Of course, there was a history between the two novelists. White had taken the trouble to get a proof copy of Hazzard’s masterpiece The Transit of Venus (1980) and had sent her a belittling account of it. It was better than her earlier work, White thought, before expertly sinking the stiletto. He told Hazzard that she was ‘still inclined to strike attitudes and pirouette around yourself but only here and there’. A quasi-apology in a later letter added to the offence: ‘To me you do seem to lead an unusually charmed life writing away in the NY apartment and Capri villa while collecting your celebrities and charmers and pairing them off around the world.’

Was it a charmed life? Privileged, of course. White’s ‘Capri villa’ was two rented rooms, but it was a place of peace and beauty. Hazzard didn’t turn aside from the realities of American political life. Her fears appear in a letter to Keene. How was it, she asked, that the nation’s vast resources were used so destructively? Writing of Reagan and Nixon, she meditated on the fact that the voters learned nothing; time after time they elected ‘imbeciles or malefactors’. Hazzard would say the same today, with the same sense of dread.

Comments powered by CComment