- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The vanished woman

- Article Subtitle: Reversing the silencing about women and war

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Near the beginning of Wifedom, Anna Funder describes a disappearing trick whereby a male magician conjures away his female assistant. She uses this as a trope for history’s tendency to make women vanish: ‘Where has she gone?’ Funder asks. This invisibility is especially the case in relation to women and war. Not only are women’s roles in wars downplayed or ignored, but women’s writing on war is seldom regarded as ‘war literature’. As Donna Coates, the author of this newly published study, Shooting Blanks at the Anzac Legend: Australian women’s war fictions, notes, the bookshelves at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra contain numerous books ‘by and about men at war’ and very few examples of women’s war writing.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Sue Kossew reviews ‘Shooting Blanks at the Anzac Legend: Australian women’s war fictions’ by Donna Coates

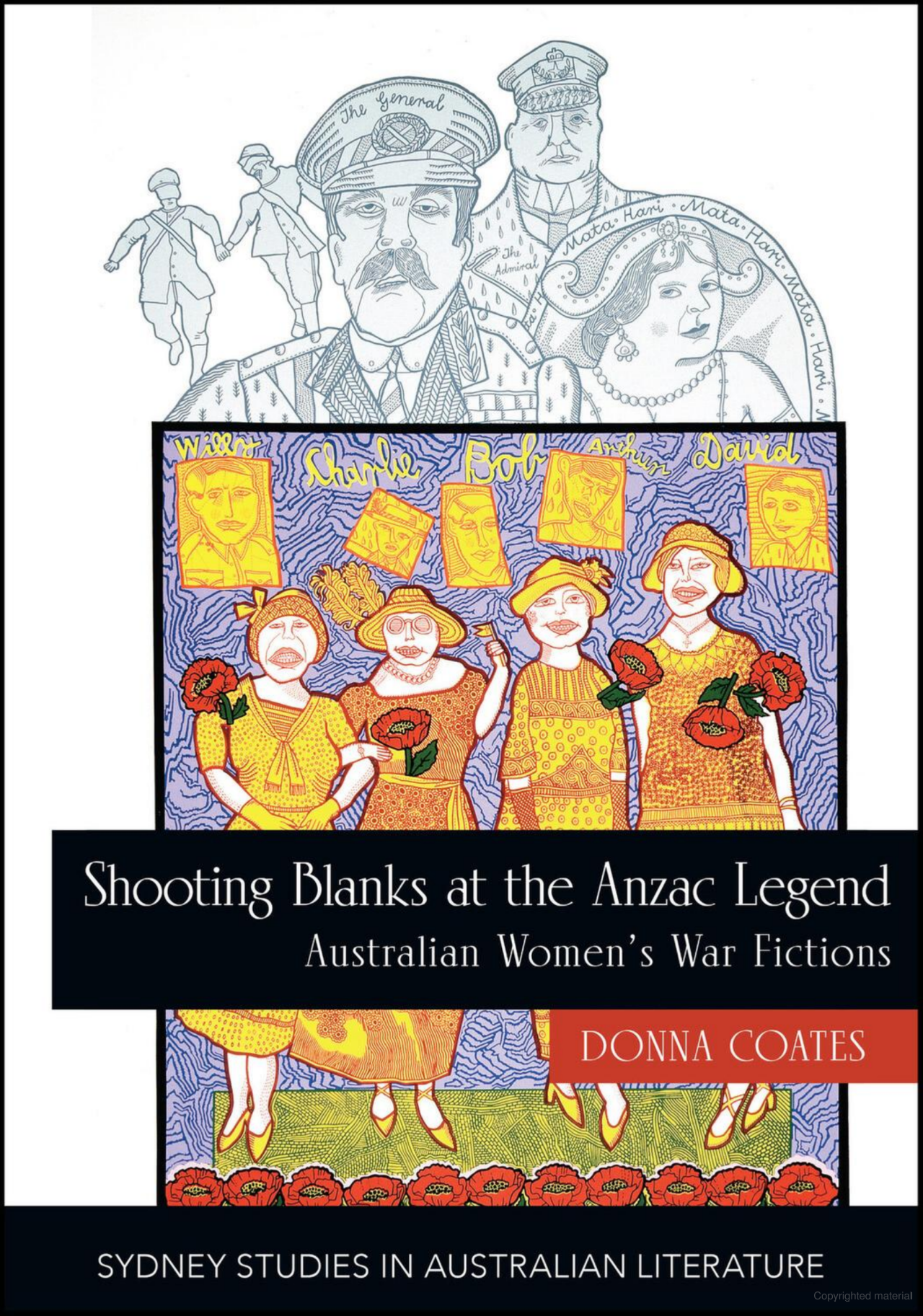

- Book 1 Title: Shooting Blanks at the Anzac Legend

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australian women’s war fictions

- Book 1 Biblio: Sydney University Press, $60 pb, 370 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

This in-depth examination of Australian women’s war fictions, written over the course of Coates’s academic career, is to be especially welcomed as a useful step in the process of acknowledging this critical gap. It is, perhaps, ironic that it has taken a Canadian academic to produce the first study of its kind. There are advantages and disadvantages to this cultural distance. Coates is meticulous in her background research and socio-historical contexts for the novels she considers, many of which have languished in obscurity or neglect. On the other hand, there is an element of judgementalism about Australian women writers in comparison with their Canadian counterparts that can sound a somewhat grating note. Moreover, there is a certain oversimplification in her reading of the Anzac legend that fails to register inherent Australian qualities of self-irony and ambiguity.

The book is divided into three parts to cover Australia’s iconic overseas wars: World Wars I and II and the Vietnam War. While many of the novels Coates refers to are written at the time of the specific war (she terms these ‘wartime novels’), others are written much later and revisit wartime history. Coates is particularly critical of Australian women writers who wrote during the Great War and who, she suggests in her Introduction, ‘muted their own voices, took their orders from [C.E.W.] Bean, and marched away to war with their soldiers’. Thus, she suggests, they were ‘shooting blanks’ rather than presenting progressive feminist ideas in their literary works. Accordingly, by failing to take on a woman’s perspective on the war, these World War I writers, including Mary Grant Bruce, Mabel Brookes, and Ethel Turner, end up ‘losing the home-front war’. There is something discordant about Coates’s prolific use of this masculinist and militaristic language to describe the ineffectuality of the work of these women writers, as in the book’s eye-catching title. It could be argued that, by constantly using these metaphors, she is herself, perhaps unwittingly, demonstrating the difficulty of situating women’s voices on war.

There are a few exceptions to her critique: writers on World War I who, in Coates’s analysis, do not merely parrot the masculinist discourses of the Anzac legend. One is Mollie (M.L.) Skinner whose ‘intrepid’ wartime novels (one, The Boy in the Bush, intriguingly co-authored with D.H. Lawrence and published in 1924) avoid this unthinking nationalism. Another is Lesbia Harford, whose novel The Invaluable Mystery (written in the early 1920s but only published in 1987 after being discovered in the archives) is, she says, the ‘only [World War I] wartime text that gives us a woman’s presence’. More recently, she argues, Brenda Walker’s The Wing of Night (2005) undercuts the ‘heroic tradition’ by challenging the Anzac legend and depicting the post-war trauma of a World War I veteran.

It is difficult in the limited space of this review to comment on Coates’s detailed readings of the very wide range of texts addressed in the book. Generally, she is as disappointed with World War II women’s texts as those of World War I in that they similarly ‘re-inscribe the values of the masculine bush ethos, bolster yet again the fighting power of the almighty Anzac, and once more assign women a subordinate place in Australian society’. She provides a detailed reading of Come in Spinner (1951), co-authored by Dymphna Cusack and Florence James, to argue that, while these writers are critical of some of the injustices and double standards faced by women in the wartime years, they ultimately reaffirm nationalist and gendered stereotypes. Coates presents a more subtle argument in discussing how World War II ‘benefitted women in many tangible ways’ as reflected in some of the fiction. Women not only found that they were quite capable of taking on men’s roles but also became romantically involved with ‘foreigners,’ including American GIs, prisoners of war, and internees, who apparently valued gender equality more than Aussie men did. While praising twenty-first-century women-centred texts that seek to ‘expose the inadequacies of the core myths of Australian society and to devise an entirely new set of stories’, she bemoans their overall lack of literary impact.

In the shortest section, on the Vietnam War, Coates shows how societal changes in attitudes to war are registered primarily by women writers who depict the ‘plight of the wounded veteran’. The texts she discusses, while politically divergent, all engage empathically with the traumatic effects of this war on its soldiers, many of whom were reluctant participants. Other little-known women’s fiction depicts the anti-Vietnam protests and the ways in which ‘the family unit became a home-front war zone’ when ideologies about the war clashed. Discussing Helen Nolan’s fictionalised account of her experiences in the Vietnam war, Between the Battles (2005), Coates considers her one of the few women who has not ‘left the writing to the men’, thereby refuting the myth that ‘women neither go to war nor write about it’.

Coates’s consistent thesis – that Australian women writers on war (with a few exceptions) have been in thrall to the highly gendered Anzac and Bush legends – is not without controversy, as some reactions to her work have shown (and as she herself notes). There is room for a more theorised intersectional feminist study that explores other aspects of this topic – paying greater attention to the diversity of contemporary Australian women writers, rather than the mostly settler-colonial version that this study largely deploys. On a more personal level, and in the interests of full disclosure, this is an area of Australian literature that I am researching, with Anne Brewster, in relation to current Australian women’s writing on war, in which we investigate how gender is implicated in the discourses and realities of war in culturally diverse literary works that discuss other wars as well as the three analysed here. For example, there are growing numbers of novels written by diasporic women who provide a different perspective on wars experienced in their own countries of origin, often through transgenerational trauma, including Asian-Australians’ responses to the Vietnam/American War.

Donna Coates is to be applauded, then, for laying the cultural and historical groundwork that provides a critical context for further feminist studies of current Australian women’s war writing. But the book’s value extends well beyond this potentially narrow endorsement. It is important in addressing what has hitherto been a reluctance to hear women’s literary voices on the topic of war, and, in doing so, contributes towards reversing this silencing, and rightfully (and at last) recognising women’s writing on war as war literature.

Comments powered by CComment