- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Like an anthem

- Article Subtitle: The life behind ‘My Country’

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

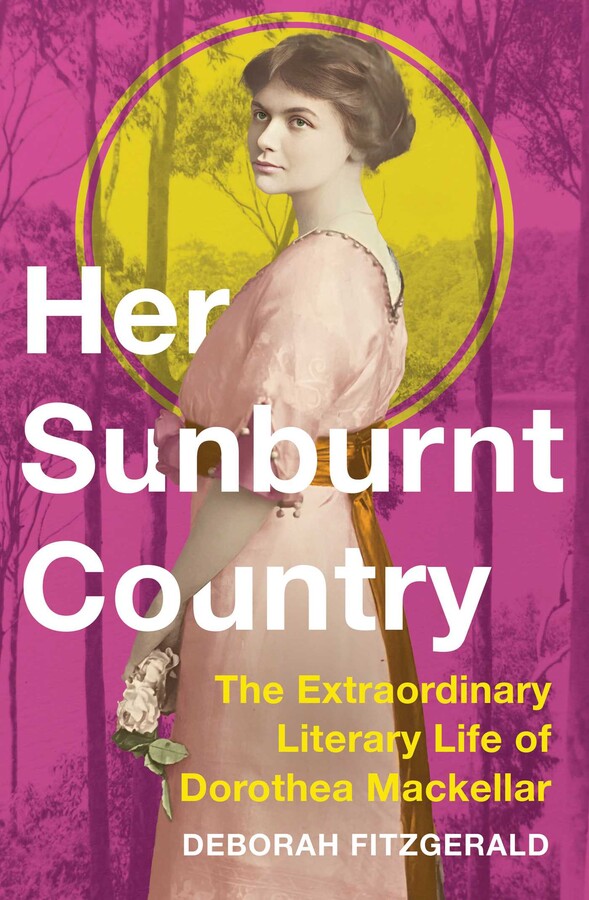

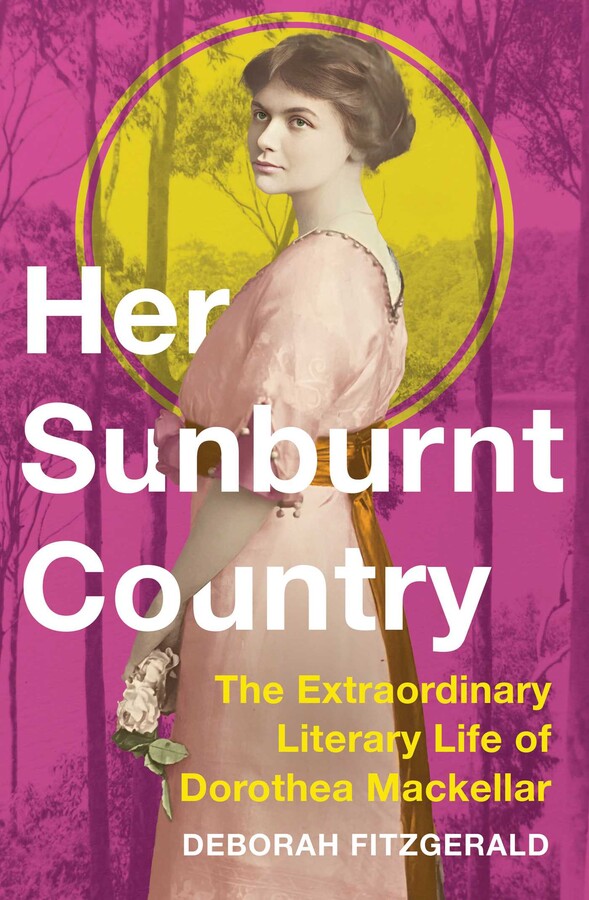

Deborah Fitzgerald’s biography, Her Sunburnt Country: The extraordinary literary life of Dorothea Mackellar, struggles to convince readers of the validity of both those adjectives. Mackellar’s life was not especially literary: she did not mix in literary circles, and had no need to write for a living, although as a young woman she published many poems in journals. Nor was it an extraordinary life, except in the sense that it was extremely privileged by her family’s wealth and social standing. It was an unusual life for a woman of her time and place, in that she did not marry; but nor did she live independently of her family until after her parents’ deaths. By then she was in her forties and had effectively stopped publishing verse.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Susan Sheridan reviews 'Her Sunburnt Country: The extraordinary literary life of Dorothea Mackellar' by Deborah Fitzgerald

- Book 1 Title: Her Sunburnt Country

- Book 1 Subtitle: The extraordinary literary life of Dorothea Mackellar

- Book 1 Biblio: Simon & Schuster, $55 hb, 330 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Deborah Fitzgerald’s biography, Her Sunburnt Country: The extraordinary literary life of Dorothea Mackellar, struggles to convince readers of the validity of both those adjectives. Mackellar’s life was not especially literary: she did not mix in literary circles, and had no need to write for a living, although as a young woman she published many poems in journals. Nor was it an extraordinary life, except in the sense that it was extremely privileged by her family’s wealth and social standing. It was an unusual life for a woman of her time and place, in that she did not marry; but nor did she live independently of her family until after her parents’ deaths. By then she was in her forties and had effectively stopped publishing verse.

Born in 1885, Dorothea was the third child and only daughter of Charles Mackellar and his wife, Marion Buckland, both from eminent Sydney families. Her father (who was knighted in 1912) was medically trained, and held a number of influential government appointments. Dorothea was educated at home. She was good at languages, and attended lectures in English literature at Sydney University but never undertook a degree. She travelled a great deal with her parents, and at times acted as translator for her father at international conferences on juvenile welfare and eugenics. She spent extended periods at the family’s country properties in the Hunter Valley and at Gunnedah.

It was a varied life, but curiously narrow. She was by no means a New Woman of the period. As her diaries testify, her days were filled with secretarial work for her parents (letters and phone calls), paying calls with her mother (these afternoons were ‘successful’, in her view, when the women they called upon were out), a little charity work, a lot of shopping and dress fittings, learning to drive, seeing friends, and going swimming; in the evenings there were parties, balls, or the theatre. She rarely reports on her reading and usually only notes that she has written some ‘verses’ (as she always called them), without reflecting on the process.

What animated her diary entries most were reports of the ‘play acting’ sessions she had with her friend Ruth Bedford, a writer mainly of verse and stories for children. They were close friends for most of their adult lives, although they never lived together, except for a couple of sojourns in London. Acting the parts of their invented characters, they would spend whole days, at the beach or at home, playing out scenes of passion and conflict, sometimes continuing the interaction in letters. This collaborative activity resulted in the publication of two novels featuring young male heroes having adventures in exotic locations: The Little Blue Devil (1912) and Two’s Company (1914). But the immediate value of the acting sessions, as Dorothea records in her diary, was to allow her to indulge in ‘obsessions’ (where she fears getting too involved in her character) or bringing her ‘relief’ (unspecified).

Reading her diary entries, and noting how frequently she was unwell – depression, fatigue, breathlessness, painful periods – left me wondering if this ‘relief’ was distraction from her physical and mental distress, some apparently undiagnosed chronic illness. Her biographer describes her as developing a dependency on alcohol as well as opiates, and disengaging from public life, after her mother’s death in 1933. She became more reclusive, and spent her last ten years in a nursing home.

Inevitably, the biographer speculates about Mackellar’s unmarried state, concluding that her subject was ‘a woman who longed for love but struggled with her sexuality and found it hard to commit to those who came in and out of her life’. It is difficult to see the evidence for this longing for love in the story, as it is told. Her relationship with Bedford seems to have given Dorothea the companionship she needed. During her twenties, she had two significant flirtations with men; the first was already married, and she lost contact with the second, an Englishman, during the war. For the most part, she treated potential suitors with mockery. I do wonder whether, as the daughter of a leading eugenicist, Dorothea may have felt that marriage and children, for someone like herself who suffered so much illness, would not be wise.

Since her death in 1968, Mackellar’s life and work have been well served by publications: Rigby’s collection of her four volumes of poetry in 1971, Adrienne Howley’s 1989 biography, based on her reminiscences (published by UQP), and a selection from her diaries between 1910 and 1918 (beautifully produced by Angus & Robertson in 1990) edited and introduced by Jyoti Brunsdon, who also went to the trouble of cracking the code which Mackellar occasionally used in her diaries.

With these books, access to the Mackellar papers in the Mitchell library, and the support of the family estate, Fitzgerald had plenty of material to draw upon. It is disappointing then that, despite the title’s claim of an ‘extraordinary literary life’, she does not attempt to fill out the literary and social-political contexts of that personal life.

For example, there is little evidence of Dorothea mixing with prominent Sydney feminists of the period. I imagine this might have been related to her father’s role in heading up the notorious 1904 Royal Commission on the Decline in the Birthrate. His findings – that this phenomenon of the 1890s (low marriage rates, and lower birthrates among those women who did marry) was caused by women’s ‘selfishness’ in controlling their fertility, and thus threatening the future of the ‘British race’ in Australia – roused the scorn of feminists. As Susan Magarey documents in her Passions of the First Wave Feminists (2001), Rose Scott berated the Royal Commissioners’ Report for blaming the woman, ‘like Adam of old’; and the radical poet Marie Pitt described the fallen birthrate as women carrying out ‘The Greatest Strike in World History’. Dorothea was not part of this intellectual and political context.

The literary context, too, is neglected in Fitzgerald’s biography. While it is true to say that Dorothea’s poetry broke with the tradition of bush ballads so popular at the turn of the century, there is no mention of her contemporaries, women writers as remarkable as Miles Franklin, Nettie Palmer, Lesbia Harford, Marie Pitt, and Zora Cross (Cross gets a mention, but only as a carping critic). Possible poetic predecessors, such as Mary Gilmore or John Shaw Neilson, are not mentioned either – except for Gilmore’s role in co-sponsoring, with Ethel Turner, Ruth Bedford, and Mackellar, the first (short-lived) PEN group in Australia.

Nor does Fitzgerald offer anything by way of analysis of Mackellar’s poetry, beyond vague references to its ‘Georgian’ qualities and her lack of sympathy with modernism (which is wrongly characterised as ‘gritty realism’). Reading through The Poems of Dorothea Mackellar, I got the impression that she was more likely to populate her bush scenes with fairies – elves and Dryads – than to elaborate on the beauties of place in the vein of ‘My Country’.

This biography is disappointing in its exaggerated claims and lack of literary and social contexts. The publishers have not helped – despite the expensive hardback production – by failing to provide either an index or a list of Mackellar’s publications.

Comments powered by CComment