- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Eyes wide open

- Article Subtitle: Gerald Murnane selects Lesbia Harford

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In her short life, Lesbia Harford (1891–1927) created a body of poems which have become increasingly important to scholars and poets in understanding both the impact of poetic modernism in Australia and shifting concepts of gender, class, and the tensions between a personal and a collective politics. While Oliver Dennis’s 2014 Collected Poems of Lesbia Harford presents Harford’s full oeuvre, the new Text Classics edition, selected and introduced by Gerald Murnane, brings a sharp and accessible focus on this seminal Australian poet, highlighting her key themes and demonstrating a literary style that straddled worlds: from the formal structures and decorous themes of late nineteenth-century poetry to the challenges to form, voice, and subject matter that characterised the emerging revolutions of literary modernism.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Rose Lucas reviews 'Selected Poems' by Lesbia Harford

- Book 1 Title: Selected Poems

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $14.95 pb, 99 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

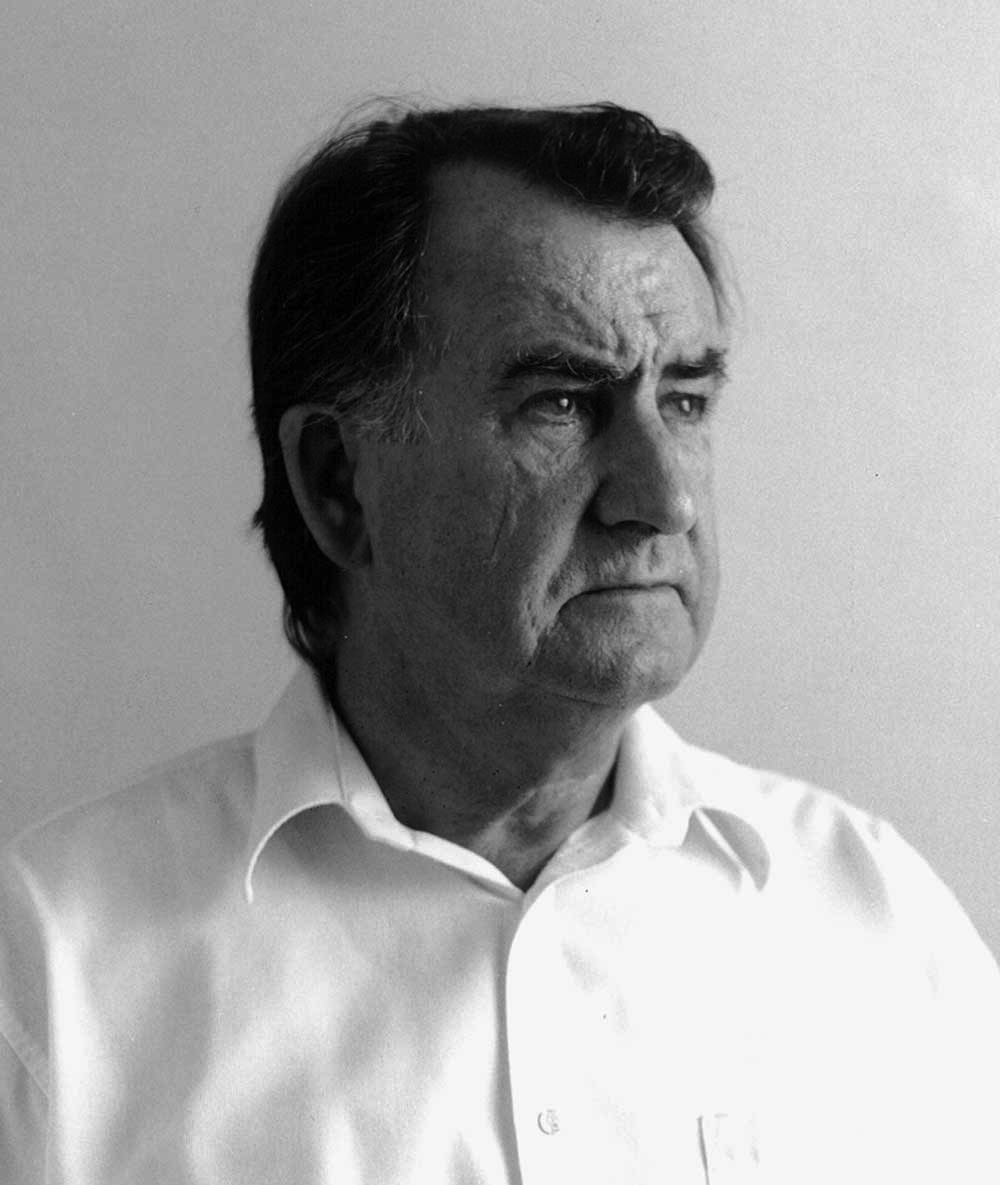

A poetry selection – especially one made by such an influential literary figure – will of course always tell us something about the selector as well as showcasing the poetry itself. In its own poetics of the meander, Murnane’s reflective introduction raises fundamental questions for any poet regarding the nature of the poem and its complex interrelations with both its creator and any imagined reader. He also helpfully draws our attention to Harford’s arresting use of rhythm – likening it to Hopkins’ radical disruptions – and the vibrancy of her imagery. As he reduces the 245 poems of the Collected down to the eighty required in this format, he describes his selection, with characteristic generosity and acuity, as a choice for ‘those that caused me … to change my view of things: that opened my eyes more widely’.

Gerald Murnane (Ian Hill/Text Publishing)

Gerald Murnane (Ian Hill/Text Publishing)

Harford pushed the boundaries of her time in terms of expectations of women and of poetry. She was one of the first female students to be accepted into Law at the University of Melbourne. Her involvement with the Communist Party of Australia led her to employment in a textile factory, where she experienced the working life and came to appreciate her fellow women workers. In poems such as ‘A Blouse Machinist’, the poet admires ‘Miss Murphy’, who is ‘nice to watch when her machine-belt breaks’; and in ‘To Look Across at Moira Gives Me Pleasure,’ her ‘red tape measure’ is described like ‘blood’ or: ‘Like a fire quickening. / It’s Revolution. Ohé, I take pleasure / In Moira’s red tape measure.’

The poet’s joy in Moira’s tape measure is not only a celebration of the beauty to be found in an ordinary situation; it indicates ‘revolution’ on a number of levels. This sensual admiration for those who labour outside a sphere of privilege also highlights Harford’s disruptive observer status: of gentile background but working in a factory; her status as a former student of the University yet a staunch anti-war/establishment critic; writing poetry of conventional lyrical beauty while also responding to a ‘quickening’ of change in ideas about identity, sexuality, and how poetry might be written.

Decades before ‘the personal is the political’, Harford’s personal life of many loves – men, women, some ‘secret’ and others not – is part of the subject matter of her poetry and, like her interest in working lives, signals a shift in how women might live. In ‘I Can’t Feel The Sunshine’, the poet tells us longingly, ‘If I should once kiss her, / I would never rest / Till I had lain long hour / Pillowed on her breast’; in ‘I Am Afraid’, she confesses her fear that ‘He’ll someday stop loving me – / That’s how he’s made.’ When she queries ‘Florence [who] Kneels Down To Say Her Prayers’, she asserts that ‘My loves are free to do the things they please / By day or night’. While Harford seems to be advocating a free and open sexuality, she is also tugged backwards towards acceptance a passive role as ‘wife’.

In the poem ‘Fatherless’, Harford aligns her own father’s absence in her life with opportunity rather than burden:

I have gone free

Of manly excellence

And hold their wisdom

More than half pretence.

For since no male

Has ruled me or has fed,

I think my own thoughts

In my woman’s head.

This opportunity to ‘think my own thoughts’, to be at least to some extent free from the constraints of class and gender and expectation is grappled with in the context of her poetics as well as her personal politics. The poem ‘Into Old Rhyme’ confirms Murnane’s observations about Harford’s challenges to expected rhythmic patterns – how, in a manner reminiscent of Gerard Manley Hopkins, Harford’s seemingly simple verse, with its unexpected deviations of rhythm and content, becomes part of the revolution in perception that she observed:

Into old rhyme

The new words come but shyly

...Swift gliding cars

Through towns and country winging,

Like cigarettes,

Are deemed unfit for singing.Into old rhyme

New words come tripping slowly.

Hail to the time

When they possess it wholly.

In the context of Australian poetry, Harford was an important initiator of such ‘new words’, even where some conventional rhyme and structure remains. Within the workshop of poetic craft, her innovations – as well as her ambivalences and legacies – contributed to new ways of seeing and living, both for women and for those who read and wrote poetry. Murnane’s thoughtful selection opens a luminous window onto Harford’s important poetry for a new wave of readers.

Comments powered by CComment