- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Gender

- Review Article: Yes

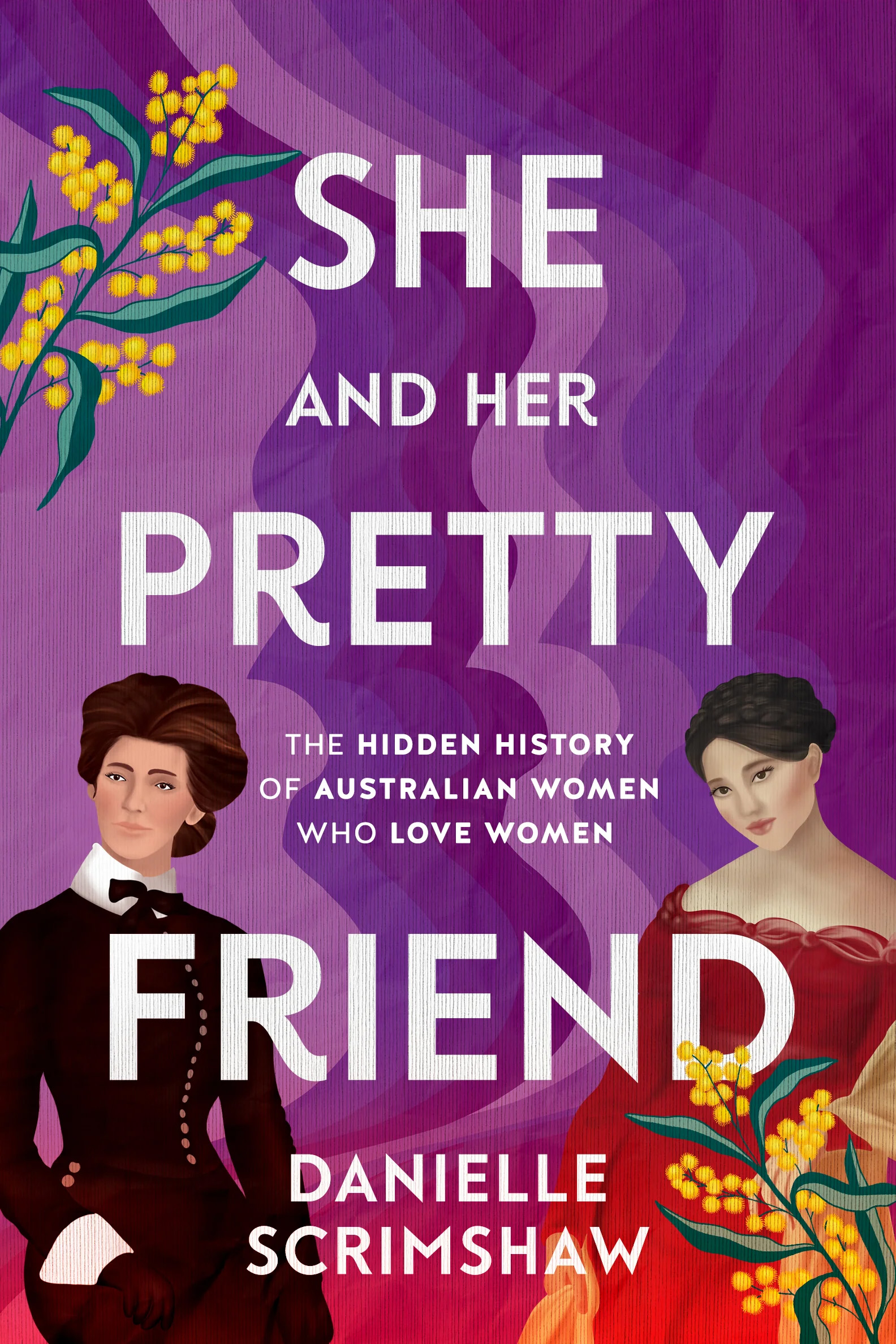

- Article Title: A rescue operation

- Article Subtitle: Queer history for the now

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

She and Her Pretty Friend is a collation of stories about lesbians in Australian history, ranging from the convict women of the ‘flash mob’ in Hobart’s Cascades prison to the lesbian separatists of the 1983 Pine Gap Peace Camp. Along the way, the reader meets a couple who farmed together in the 1840s, another couple who taught swimming and started the first women-only gym in Melbourne in 1879, as well as one of the first women doctors and her lifelong companion, who both served at the Scottish Women’s Hospital in Serbia in 1916. There are other figures, like poet Lesbia Harford and her muse, Katie Lush, or suffragist Cecilia John, who rode on horseback, dressed in suffrage colours, at the head of a march of more than 4,000 women and children (Danielle Scrimshsaw credits her with ‘queering the suffrage movement’). A chapter on Eve Langley and other ‘passing women’ prompts questions about whether they would have seen themselves as transgender, in today’s parlance.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Susan Sheridan reviews 'She and Her Pretty Friend' by Danielle Scrimshaw

- Book 1 Title: She and Her Pretty Friend

- Book 1 Biblio: Ultimo Press, $35.99 pb, 280 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

She and Her Pretty Friend introduces a variety of women whose stories touch on major events in settler Australian history, mainly from the period 1870–1930, including the suffrage campaigns, socialist ideas, World War I, and women’s participation in both frontline support and protests against conscription, as well as the theatre world, the university, the physical culture movement. These events are sketched into the stories, but at times the interpretation of the characters’ actions fails to take account of the context of ideas in which they were embroiled. Especially in the decades before 1914, there was a heady mixture of new ideas about reforming the social and sexual order informing the rising movements for workers’ and women’s rights.

The book’s catchy title comes from William Chidley, one of my favourite characters from the radical 1890s. He was describing an actress who, he believed, had seduced his common-law wife Ada, who was also an actress. This Miss Freudenberg, he wrote, would desert any young man who had escorted her home from the theatre ‘and retire with her friend, eyeing her as a cat does a mouse … she and her pretty friend’.

Scrimshaw scolds Chidley for this ‘biased account’ of the women’s relationship ‘as a binary of active and passive’, of predator and victim. But she seems to be unaware of what a sex radical he was, or how he was persecuted for his ideas. He would go about the streets dressed in a Grecian tunic and sandals (a male version of Rational Dress) and give public lectures on his theory that conventional heterosexual copulation (which he dubbed the ‘crowbar’ method) should be replaced by an act based on mutual attraction in which the woman would be the initiator and the penis would be drawn into the vagina as into a vacuum.

Chidley was influenced by the new breed of ‘sexologists’, notably Havelock Ellis and Edward Carpenter. It is interesting that Ellis, too, was married to a woman whose sexual preference was for her own gender. Chidley may have expressed his jealousy about Ada’s passion for her sister actress in conventionally sexist terms, but he would also have been familiar with Carpenter’s theory of ‘Urnings’, the third or ‘intermediate’ sex, which gave support to many people whose sexual identity did not conform to heterosexual norms.

The chapter about Chidley, Ada, and Miss Freudenberg is one where the book’s presentism is very evident. Scrimshaw understands that women’s sexual desires were ignored in the historical record, but she does not seem to perceive that when women were deemed to be sexually passive by nature, there could only be one explanation for lesbian desire – the seduction of a victim by a ‘pervert’.

For most of the book, however, the breezy style expressing the historian’s desires and pleasures works well. I could not help smiling at the comment that the New Women riding bicycles with their divided skirts ‘sound like nonbinary icons’. Nor could I help applauding a writer who had the temerity to disagree with the editor of Anne Drysdale’s letters, who said it would be ‘futile as well as pointless’ to speculate, in the absence of evidence, about the sexuality of Miss Drysdale and Miss Newcomb – and then to use this phrase to conclude: ‘It would be futile as well as pointless to believe queer women did not exist outside a frighteningly narrow set of expectations.’

She and Her Pretty Friend, this ‘love letter to the queer women who paint the history books lavender’, is often romantic in tone. Scrimshaw tells us a good deal about her various crushes, with charming stories about her girlfriend, and expresses romantic ideas such as, ‘there is something fundamentally sapphic about travelling for love’.

Gay romance is all the go – did that come with marriage equality? I see that two young women of the author’s age announce their engagement in the newsletter of their old school, alongside the weddings of their heterosexual classmates. In a different school, as ‘out’ lesbians, they might have been prevented from taking up leadership roles, or even from enrolling at all. Queer visibility, queer stories are crucial; and yet homophobic backlash must be confronted again and again.

Comments powered by CComment